Winter 2024 Antler River Art Review

Etienne Lavalle

Thu January 16, 2025

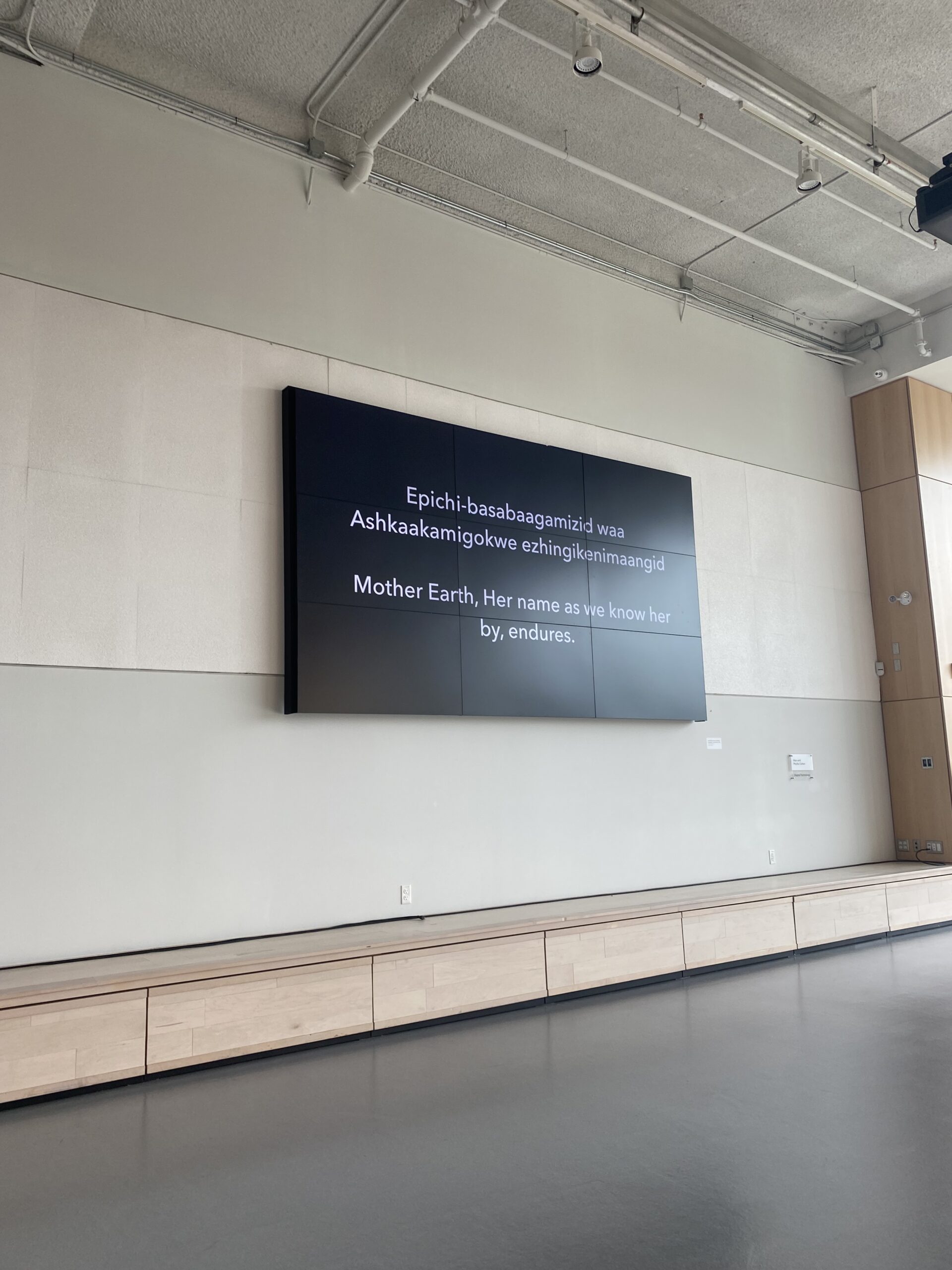

Baapaagimaak: Weaving Endurance by Katie Wilhelmina and Summer Bresette

Indigenous resilience takes many forms. The shifting shape of endurance in the face of

devastation manifests in digital video form at Museum London. Basket weaving is a part of the

Anishinaabe way of knowing and being. Indigenous ways of being are not compartmentalized.

Basket weaving is interconnected with community, family, craftsmanship, oral teachings, and

with the plants and trees from which the basket supplies are harvested; basket weaving thus

represents a complex relationship between human and non-human persons, which is echoed by

the complexity of the basket form itself.

The video exhibition is an array of natural images: trails, dappled light through branches, pieces

of bark, vivid blue skies, and small green areas. As a moving collage of the natural world, it

becomes a narrative about survival, and the complex responses of Anishinaabe people as part

of the land’s ecosystem.

The writing of the Ash Borer beetle on bark is the symbol of environmental catastrophe. This

invasive insect, which came with settler colonialism, is responsible for ecosystem loss. The

calligraphy of the Ash Borer resembles the winding path of our river, the Deshkan-ziibi, through

the land. Like all other aspects of the film, this is a reminder that the land functions as a teacher,

and all that lives on it is a teacher. Katie Wilhelmina and Summer Bresette have much to teach

our city, and by extension, the world.

Tom Wilson Tehohåke – Indigenous Truth Telling through Art

Tom Wilson’s TAP exhibition tells the story of Mohawk resilience, cultural resurgence, and the

lasting effects of residential school on families. Wilson discovered his Mohawk heritage and

began to reconnect to his people at the age of 53.

Pointillistic dots are crowded in with spidery, frequently indiscernible script, referring to the

colonial linguistics of the English language forced upon Indigenous ways of being. Clusters of

dots mingle and separate like communities. Abundant use of colour pulls from the biodiverse

woodland landscape of flowers. Natural motifs of crows and fish speak to the reconnection to

non-human relations.

Most intimidating are Wilson’s nun figures. These imposing figures resemble the Grim Reaper, a

fitting allusion when so many First Nations children met their death at the hands of the Catholic

Church. The nuns have no faces except for a red crucifix in place of eyes, as these women

abandoned their humanity for a violent, cruel ideology. Not only is this a reminder of a lack of

humanity at the heart of colonization, but a reminder about the perceived purity and kindness of

white women.

Let this exhibition be a reminder to our readers to engage in the stories of survivorship of FNIM

people. Please take a moment to read, at the very least, the Child Welfare and Language

Sections of the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action.