“Portrait of Elliot”: Painting of brain cyst stars at neuroscience conference

Incé Husain

Sun May 18, 2025

At Museum London on February 20th, a painting of a glowing brain is displayed on an easel. The stylized MRI brain scan, from the back-of-the-head view, is aflame in yellows and reds that form a hazy halo around a starburst of highlighter-green brain fluid. Folds of pale coral-coloured grey matter coalesce into cranial nerves bordered by a streaming blue-violet neck. In the right hemisphere drifts a ghostly cyst.

The piece is called “Portrait of Elliot”, painted by artist Natasha Beaudoin. It is based on a real MRI scan of her boyfriend, Elliot Tomlinson, who was diagnosed with an arachnoid cyst.

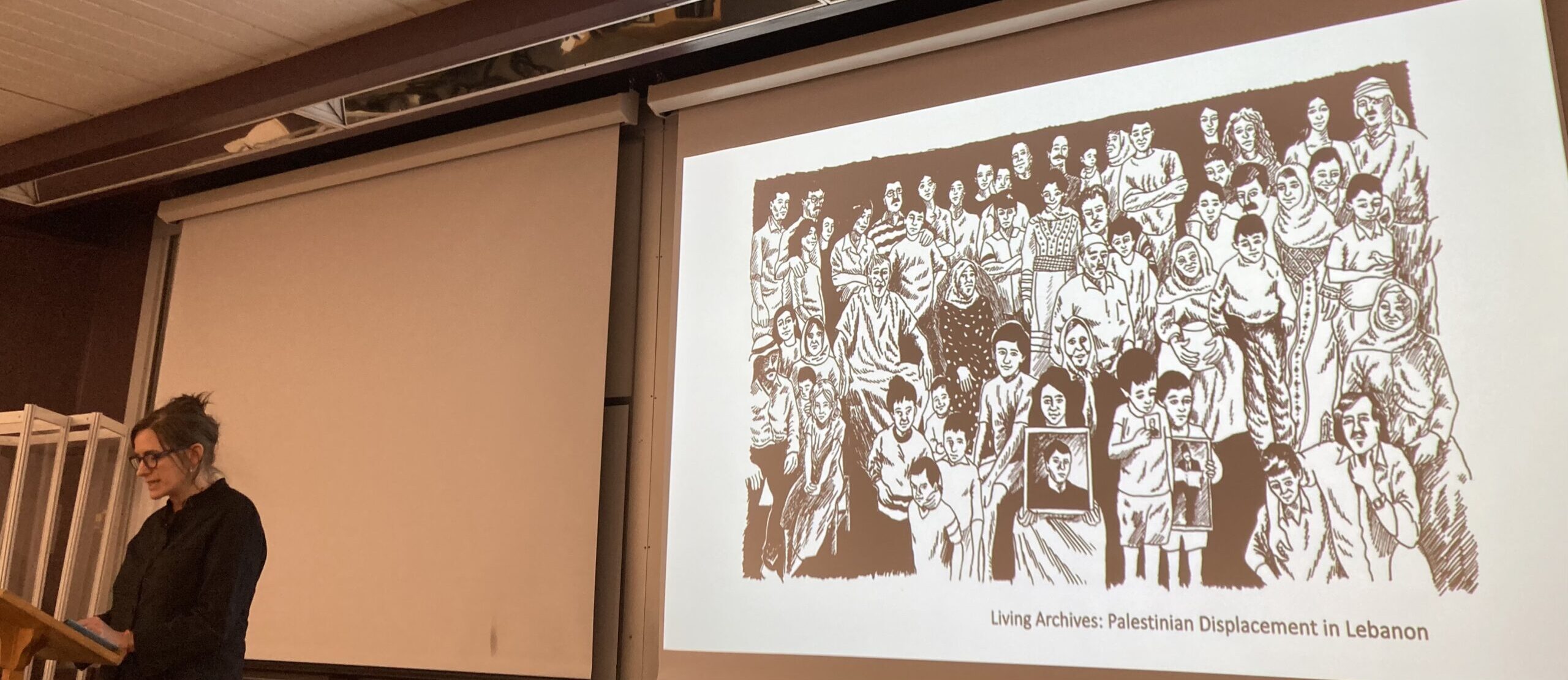

Beaudoin submitted the painting to the “Brain Art Exhibit” event of Neuroscience Research Day, a student-organized conference held by Western University’s neuroscience program. The event aimed to showcase neuroscience topics through art.

“I wanted the focus obviously to be on the brain and where the cyst is,” says Beaudoin. “I kept the central internal piece more warm tones and yellow tones because Elliot’s favourite color is yellow…the cool colours kind of vanished into the dark. I have a weird colour association with people, I feel like certain things must be a certain colour.”

Students, faculty, and community members filled the room, weaving between the artwork and neuroscience research posters. Among them was Tomlinson.

“I think the painting is really captivating to me because, having sat through the MRIs before and seen them printed out…Natasha’s choice of all the bright colours ends up looking just like the way that they come out,” says Tomlinson. “It looks just like the colourized ones.”

Beaudoin painted with acrylics using airbrushes, which use pressurized air to create hazy sprays of paint. She would load the brushes with pigments and splay them across the canvas in blasts of air, pre-planning her sequence of colours for a speedy process that fights “against the clock” of the rapidly-drying paint. She finished the piece in about five hours, painting in forty-five minute increments at most.

“I had to do it in small segments,” says Beaudoin of her process. “It was a very timely, rapid situation.”

“Just like a real MRI!” Tomlinson says.

A first year MFA candidate at Western University, Beaudoin’s “Portrait of Elliot” was also a response to faculty feedback that urged her to “showcase a person without actually showing who they are.”

“How do I draw a portrait without a person being present?” says Beaudoin. “How much information do you actually need to consider something a portrait? When you lean into abstraction – which is not something I’m very comfortable with – how much is their presence back in there? Do I still see Elliot within this? Have I lost him within the piece?”

Tomlinson’s cyst was diagnosed after a minor concussion at age ten that left his vision badly disrupted. The MRI scan that followed showed a congenital arachnoid cyst in his blood-brain barrier. Though such cysts are benign, Tomlinson’s concussion had made the cyst swell and graze his optic nerve, the fibre bundles that transmit what we see to our brains. Doctors advised him to cease playing contact sports and to avoid situations that might similarly exacerbate the cyst. He shifted to individual sports, such as paddling and hiking, and discovered all the activities he loves to do now.

“The things that are a big part of my life now did actually come out of that original diagnosis. It is something you can live your whole life without noticing, but there are some pretty big advantages if they do catch it,” says Tomlinson. “The cyst structure is a lot more fragile than normal brain tissue. So I just have to be more cautious. My skull is thinner around there as well.”

Tomlinson was subtly involved in creating “Portrait of Elliot” himself. He had gifted airbrushes to Beaudoin and practiced with them on the canvas that became her piece. The canvas journeyed through different scenes and mediums, unfinished and experimental. Re-sanded and primed, it was a night sky from a shared camping trip, a memento from a video game, work with watercolor, oil, pastel. Beaudoin and Tomlinson had been discussing MRIs and Tomlinson’s experience at the Sick Kid’s hospital peripherally as the canvas changed. Finally, Beaudoin “mixed the two together”. She gazed at the MRI scan for a few seconds, let it sink into her mind’s eye, and got to work.

“What I saw was her experimenting until something stuck,” says Tomlinson.

An engineering and physics student at McMaster University who previously worked in insurance, Tomlinson sees art as an “antidote” to the technical thinking that surrounds him.

“My background is all very technical. We don’t have a lot of exposure to art,” says Tomlinson. “Being exposed to Natasha’s process is inspirational, a relief, a motivation… It feels like it brings a lot of meaning to things that I do where there’s not a lot of room for expression or beauty, where everything is standardized, essential, functional. It’s an antidote.”

Beaudoin gravitated to art because of a language disability. Art offered her a means of expression where words couldn’t.

“I had a challenge of using words to describe what I was trying to showcase, so I quickly developed into art because it was a nice way for me to communicate to my family members. My parents encouraged it, especially when I was younger, because a lot of time, depression would occur.”

Her dream is to teach art as a professor, pairing her love of art and teaching. She completed a major in fine art at Queen’s University and minors in art history and business. At Western, her thesis relates to portraying Gen Z-related experiences, social cultures, and friendships.

“I’m a very selfish painter,” says Beaudoin. “I find people very interesting. I’m not going to paint what I don’t like. I love my friends and people I’m close with, so that’s what I’ll do.”

Beaudoin describes her style as “overly-saturated and digital portraiture.” She begins with photo references, digitally manipulates them with infusions of colour, and then greets them with paint strokes that turn them into “traditional oil portraits.” One artwork portrays Beaudoin’s memories with Tomlinson; she describes it as “meshing all our worlds into one piece.” The work is a blend of a place where they hiked together, Tomlinson playing minecraft, and other shared details.

“It comes to me right away or sometimes I arrive to it,” says Beaudoin of the vision steering her pieces. “When I manipulate the image, I’m keeping a sense of, when was it taken, who is in the picture, trying to keep parts of their personality with it. I work backwards when I create. I think of an image then work with it, then come to the realization of what it’s supposed to represent. So, complete opposite of what usually artists do. It’s a very funny process for me.”

Beaudoin hopes to “reestablish” the academic art world into a culture that is more open to diverse artistic backgrounds and a plurality of artist relationships to creation. She shares that the art world requires her to exclude artists on Instagram as inspirations for her thesis because they aren’t academically established. The art world also requires artists to “justify everything” about an art piece, at the cost of surrendering intuitive feelings of beauty and joy.

“Why canvas? Why that size? Why the colour? Why the application? Every single detail – it becomes suffocating to have to justify every single part of the process,” says Beaudoin of the academic art world. “It’s nice to create something where you don’t have to justify everything. It’s nice for something to be plain and simple, a beautiful piece, just enjoy it being beautiful.”

Showcasing art at Neuroscience Research Day was a welcome escape from the art world’s “posh” standards. Beaudoin was excited that attendees engaged with the art and warmly asked her questions about it. She was happy with “Portrait of Elliot” being “a pretty picture” that didn’t require onslaughts of artistic justifications.

“I think people underestimate the academic rigor, especially at her level, of being in the art world,” says Tomlinson. “It was really nice to see Tash just express herself without those restraints.”

Attendees at the Brain Art Exhibit met Tomlinson with an “earnest curiosity” about his cyst, a deviation from the “apprehension” he usually receives.

“Pretty often when people learn about someone’s congenital condition or something disordered or something related to the brain, there’s a lot of stigma or apprehension about it. I was really happy to just be met with an earnest curiosity about it,” says Tomlinson. “It was a really uplifting experience to be asked about my condition without any of the stigma around it.”

The stigma Tomlinson feels is often rooted in people’s unfamiliarity with cysts; they may equate them with malign tumors and misassociate a severity to his life that constricts their interactions with him. This was not the case in a room full of neuroscientists and brain enthusiasts. Tomlinson shares that “Portrait of Elliot” and the academic nature of the event “completely broke the ice” and allowed for free conversation.

“Some people have their preconceived notions about what a cyst means… It’s like the expectation that ‘he’s got a birth defect, deformity in his brain, shouldn’t that make him weird?’” says Tomlinson. “When someone is receptive to being educated about the difference [between a cyst and a tumor], that goes a long way for me…[Stigma] doesn’t come up too frequently in my life, but when it does, it is usually a source of a sense of apprehension for me. Not anxiety, but having to find the chance to educate them. It comes with a bit of baggage for me. But [the event] was not like that at all and that’s thanks to Tash.”

With fanciful hors d’oeuvres cradled in napkins, attendees flocked to artworks and submitted votes for their favourite piece. The top-voted art piece would bring in a $200 prize for the artist. “Portrait of Elliot” drew eyes, hearts, and minds throughout the hour-long exhibit, and Beaudoin won.

Tomlinson shares that his parents love the painting. They love the fluorescent colours that echo the actual hues of colourized MRI scans.

“If anyone wants it, they can have it,” Beaudoin says of the painting’s fate. “I don’t really sell my art often. I was just going to give it to Elliot.”