“The world is a relative”: How language can heal the Earth

Incé Husain

Sun November 24, 2024

On Thursday, October 17th, Potawatomi botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer gave a talk at Centennial Hall on how Indigenous teachings encompass protection and love of the Earth. Indigenous languages hold a worldview where the land and all beings are relatives; this inherently disallows destruction of the Earth.

“If the world is a relative, there are boundaries on what can be taken,” says Kimmerer. “There are guidelines on what we consume… Use everything you take. Take only what is given. Understand them as gifts, not commodities. Corporate messages confuse us about what we need and what we want.”

Her voice was rich, deep, and soft, emanating from the stage to a packed auditorium of students, professors, and community members.

We “it” the world

Kimmerer conveyed how language imposes morals onto a people and dictates where they steer violence. English objectifies nature, justifying nature’s destruction; the Earth is not a relative, but a thing, an “it”.

“Interrogate the word ‘it’ as we consider the gift of language. We “it” the world. English paralyzes us and demands objectification,” says Kimmerer. Her PowerPoint slide beamed with a monarch butterfly, a salamander, a black bear, the moon and the ocean – all reduced in English to an “it”.

“If I called my grandmother, or the person sitting across the room from me an “it”, that would be so rude, and we wouldn’t tolerate that for members of our own species,” Kimmerer elaborated in a 2019 interview. “But we not only tolerate it, it’s the only way we have in the English language to speak of other beings – as ‘it’.”

Kimmerer says the consequence of objectifying nature is “moral exclusion”, a total severance from feeling any concern for the Earth. This underlies an unregistered ease with causing the Earth damage.

“Moral exclusion is the consequence,” she says. “It is much easier to say “harvest it” than “we cut her down”. Is there a way to heal English from this wound of objectifying the world?”

She shared that the Anishinaabe word “Bmaadiziaki” means “Earth Being”. She suggests that it might be shortened to “ki” for use in English as a pronoun to refer to nature. This could restore linguistic life to nature, removing the premises for harm. Instead of the word “it”, “ki” could be used for plants, animals, land, and all else that is not man-made.

“[Ki] are the lives of others who are keeping me whole,” says Kimmerer.

She calls “ki” the “pronoun of the revolution” for its recognition of nature’s personhood. In a 2019 interview, Kimmerer said that she was wary of “appropriating” Indigenous culture by offering “ki” to English, but then realized that the sound ”ki” also exists in other languages to refer to beings. For example, the word “qui” means “who” in Spanish and French; the plural for “ki” is “kin”, which already exists in English.

“When I’m tapping my maples in springtime, I can say “we’re going to go hang the bucket on ki,” Kimmerer lists examples in the 2019 interview. “When the geese are flying overhead, we can say “kin are flying South for the winter.” Everytime we speak of the living world, we can embody our relatedness.”

Two-eyed seeing

Kimmerer clarified that recognizing nature’s personhood does not mean attributing human traits to nature. Rather, it means acknowledging other beings’ unique experiences of life.

“What I mean when I talk about the personhood of all beings, plants included, is not that I am attributing human characteristics to them. Not at all,” said Kimmerer in 2019. “I’m attributing plant characteristics to plants… I think it’s deeply disrespectful to say that they have no consciousness, no awareness, no beingness at all.”

Indeed, Kimmerer added that recent scientific studies show that other beings experience life with lushness and complexity.

“I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants or animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite – what we’re revealing is the fact that they have a capacity to learn, to have memory, and we’re at the edge of a wonderful revolution of really understanding the sentience of other beings.”

She urged the audience to think of their connectedness to land.

“Is land a source of belongings or a source of belonging?“

She says the West treats ecosystems as “machines”, a “collective of interacting parts with humans in charge”. Land is merely property, a “capital for resources”.

In Indigenous teachings, land is “identity”. Land is the sustainer, the teacher, the healer, “inspirited and alive”. Land is sacred, inseparable from Earth Beings and laden with ancestral connections. She expresses gratitude for each breath of morning air, sweet water to drink, the sound of geese in the skies, the gift of a purpose-driven life.

“How have our worldviews been colonized? What are its consequences? What do we do about it?” says Kimmerer. Behind her, the PowerPoint slide bears the image of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School that vowed to “kill the Indian, save the man”; rows of children, stripped by the school of their language and being, stare bleakly. “Erasure of Indigenous languages is one of the most potent tools of colonization.”

As the climate catastrophe intensifies, Kimmerer says scientists are turning to Indigenous teachings for a path to restore the Earth. She shared a 2019 UN report that shows a massive decline in biodiversity; this decline is attenuated in lands stewarded by Indigenous peoples:

“Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about 66% of the marine environment have been significantly altered by human actions. On average these trends have been less severe or avoided in areas held or managed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.”

Kimmerer believes in an “intellectual polyculture” that draws from both Western science and Indigenous ways of knowing to protect and cherish the Earth. Western science can be guided by Indigenous values embedded with emotional and spiritual knowledge.

“Those two kinds of knowing are human knowledge,” says Kimmerer. Sweetgrass – gold and braided – beams on her PowerPoint slide, a metaphor she uses for entangled knowledge. “[Sweetgrass is] the Hair of Mother Earth. We braid her hair out of tender love and regard. These strands are Indigenous knowledge, Western science, and the teachings of plants.”

Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass, is a series of essays that form this braid. Her scientific expertise as a botanist weaves seamlessly with Indigenous teachings honouring plants as teachers. In a 2019 interview, she summarized that “science polishes the gift of seeing” by offering instruments, like microscopes, that allow us to “extend our eyes into other realms”. Indigenous traditions “work with gifts of listening and language” that nurture emotional, intuitive understandings of existence that clarify life’s meaning.

“(Science) brings us to an intense kind of attention to the natural world, and that kind of attention also includes ways of seeing quite literally through other lenses. We might have the magnifying glass that allows us to look at moss with an acuity that the human eye does not have, so we see more,” says Kimmerer in 2019. “But we’re in many cases looking at the surface, and by the surface I mean the material being alone. In Indigenous ways of knowing, we say we know a thing when we know it not only with our physical senses, with our intellect, but also when we engage our intuitive ways of knowing – of emotional knowledge and spiritual knowledge. What is the story that being might share with us if we knew how to listen as well as we know how to see?”

One essay from Braiding Sweetgrass, “Asters and Goldenrods”, tells the story of how Kimmerer came to be a botanist. She writes lovingly of asters and goldenrods, describing how their respective deep purple and gold flowers vibrantly intertwine in shared bursts of colour.

“I was born a botanist,” says Kimmerer. “Asters and goldenrods, with monarch butterflies, would bloom around my birthday. I would stand shoulder to shoulder with them.”

Kimmerer, struck by their beauty, wondered why asters and goldenrods intermingled instead of growing apart.

“I thought that, surely, in the order and the harmony of the universe, there would be an explanation of why they looked so beautiful together,” she said in 2019.

But this curiosity was not welcomed by academics at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry where Kimmerer enrolled, who deemed the question completely isolated from the scientific study of plants. They urged her to pursue art if she was interested in aesthetics, resolute that feelings about beauty should not guide scientific inquiry.

Kimmerer, demoralized, said she had “no vocabulary for resistance” as she witnessed the dismissal of her intuition. Now, she believes this disregard echoed the assimilationist views embodied by residential schools, imposing the Western worldview as absolute truth.

“The things I knew weren’t valuable,” says Kimmerer. “What does it mean to be educated? To be an educated person? Teaching everyone to think the same is not. It’s when people know their gifts and how to give them.”

Indeed, Kimmerer’s contemplation about the vibrant, shared growth of asters and goldenrods yielded a scientific answer.

She explains in a 2019 interview that their deep purples and golds are complementary opposites on the colour wheel, meaning they are among the most vivid colour pairs in the world and that their light beams combine to give white light. This vividness attracts far more pollinators to each flower than if asters and goldenrods grew apart.

“It’s a question of aesthetics as well as ecology. Each of those plants benefit by combining its beauty with the beauty of the other. And that’s a question that science can address, certainly, as well as artists,” says Kimmerer in 2019. “I just think the question “why is the world so beautiful” is a question that we all ought to be embracing.”

Now, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry boasts a Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. The Center aims to instill budding scientists with understandings of how to wield scientific tools within Indigenous worldviews.

“I think we can train better scientists when there is a plurality in ways of knowing, when Indigenous knowledge is present in the discussion,” said Kimmerer in 2019. “When students graduate, they have an awareness of other ways of knowing, they have this glimpse into a worldview that is very different from the scientific worldview. I think of them as being stronger and having the ability for what’s called “two-eyed seeing”, seeing the world through both of these lenses, and in that way having a bigger toolset for environmental problem-solving.”

Sharing with the Earth

Kimmerer shares teachings that guide how we can sustain ourselves in relation to the Earth, acknowledging that we are “consumers”.

“We have to consume because we’re animals, but how we consume is important,” says Kimmerer.

Self-restraint and sharing are inherent in these teachings. For example, when picking blackberries, she says that we must “never take the first one we see” but the “fourth or seventh”. This will ensure that an abundance remains. We must also ask “permission” to harvest blackberries. This permission comes from attentive interactions with plants, such as the ease with which a blackberry may fall into our palm when picked. Kimmerer calls this attentiveness a way of “asking for the life of their offspring”.

“Sunshine, water, wind, is given,” Kimmerer gives a sense of gifts and granted permissions. “Tar extraction is not.”

In 2019, the UN released a report on the rights of Mother Earth, titled “Harmony with Nature”. It summarizes humankind’s “evolving consciousness” of interconnectedness with the Earth:

“The present commemorative report highlights humankind’s evolving consciousness of our relationship with Mother Earth, an evolution manifested worldwide through legislation, policy, education and public engagement, all guided by the urgency to protect Mother Earth and to transition to an Earth-centred paradigm.”

One subheading in the report, “National legislations adopted to grant rights of Nature”, lists instances across the world where the personhood of all beings are now legally recognized.

For example, the High Court of Bangladesh granted the Turag River legal person status and ruled to remove all establishments on its banks; the Federal Supreme Court in Brazil granted rights to non-human animals in order to “advance interconnectedness between human beings and Nature”; and the Parliament of Uganda issued an Act attesting that “nature has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions, and it’s processes in evolution”, with all people legally allowed to bring to court instances where these rights are violated.

“Land as family, sacred responsibility, finds its way into international law,” Kimmerer summarizes.

Her talk ended with a question session. The audience submitted questions on an online platform; a talk moderator chose some to read.

How do we honour invasive species that harm the ecosystem? asks one audience member. How do we get rid of fossil fuels when they will only be replaced by equally damaging cobalt and lithium? How do we talk with people who don’t understand that the Earth is a relative? How do we remain hopeful in these violent times?

Kimmerer suggests meeting invasive species with humility – to acknowledge that they “are here for a reason” and can be moved to other places where they maintain the balance in an ecosystem. She says that cobalt and lithium may not be the answer to fossil fuel reduction at all, but feed into a “colonizer mentality” that equates progress with greater consumption.

“What do you need?” Kimmerer responds. “What if we change ourselves instead and reduce our own consumption?”

Those who have difficulty grasping interconnectedness with the Earth may be moved by stories.

“I find it hard to be moved by someone who tells me what to do and what to think,” says Kimmerer. “Invite people to look at something differently. Try to do it with story, to obliquely tell them about something. It is a seed – if the soil is fertile, it will grow.”

Hope can rise from an internalized awareness of impending climate catastrophe. Kimmerer tells the story of one of her students, who lives with incredible vigor knowing that the world teeters with fragility: she knows that none of her decisions are inconsequential.

“When everything hangs in the balance it matters where I stand,” Kimmerer quotes her student. “I have the privilege of living in a time when every decision I make matters to all of humanity.”

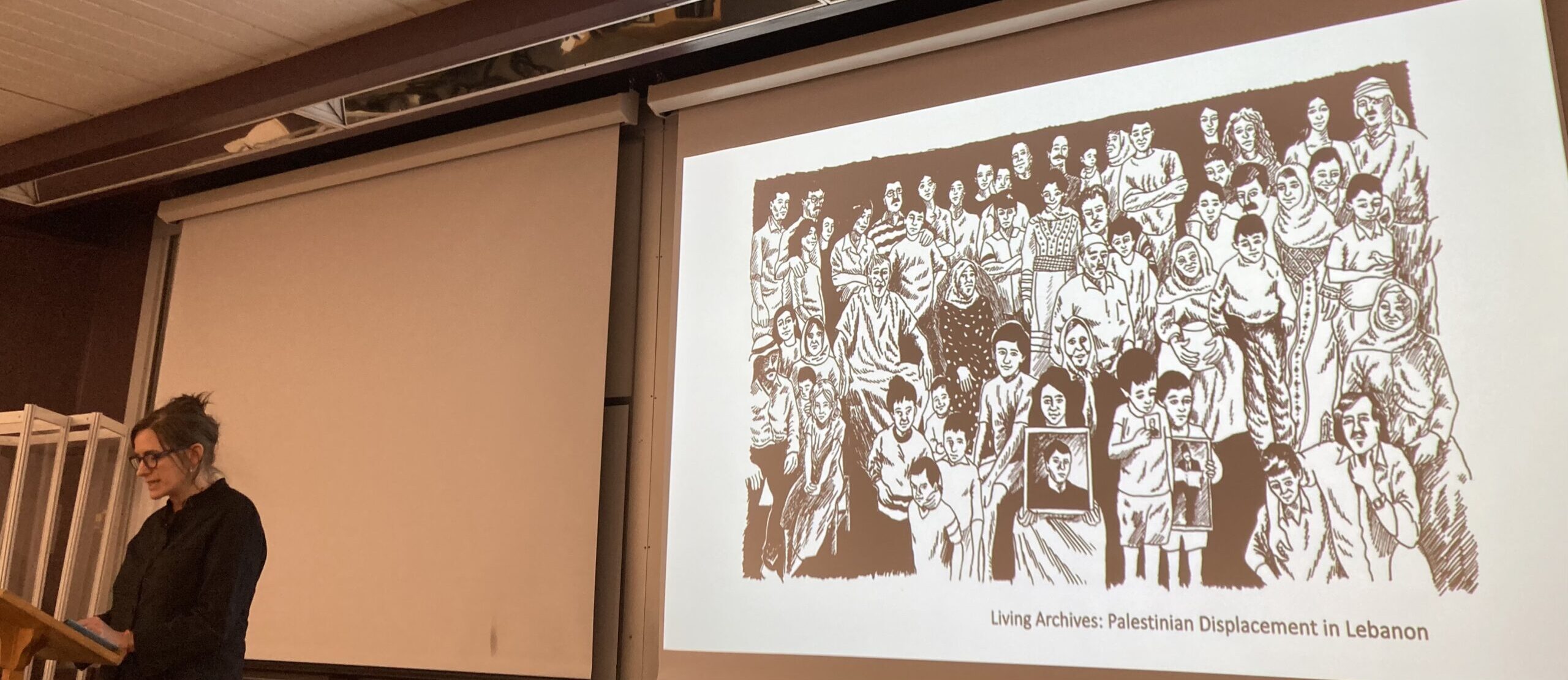

Gifts from Palestine

After her talk, Kimmerer was invited to some classes at Western University through the office of Indigenous studies.

Dina Dwairi, a third-year student completing an honours specialization in environmental science, attended Kimmerer’s talk and met her in the course “Land Healing and Responsibility”. Braiding Sweetgrass is a required course reading.

“It was an incredible experience,” Dwairi says of meeting Kimmerer. “I had been reading the book throughout the semester, and when I got the opportunity to see Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer I was ecstatic. She’s truly such an inspiration… Her presence is incredible. She’s captivating with the way she speaks and even though I read the book, every second of her talk was even more valuable. She’s very charismatic. When you read her book you understand the hardship she pushed through to be where she is, and I think that is the most inspiring thing for me.”

Dwairi resonated with Kimmerer’s identity as a woman of science and a woman of tradition. Jordanian and Palestinian, Dwairi is deeply bonded to her traditions. She says much of her knowledge came from her grandmother, who tended lovingly to the nature around her. Dwairi has seen the way this traditional knowledge is “discredited” in the West, and considers Kimmerer a “role model” for pioneering the coexistence of scientific and traditional thought. Braiding Sweetgrass has sold over two million copies worldwide and has been translated into twenty languages.

“I lived all my life in Jordan and I came here to study. A lot of the knowledge I have came from my grandma. But when you come here, that is no longer existing,” says Dwairi. “I think part of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book talks a lot about — “how can we overlook the knowledge of women who have sat and watched and taken care of the environment around them and try to somehow discredit that?”. That really stuck with me. And that’s why, for me, she is such an inspiration of how it is hard to be different in spaces like this – but fighting for it and not erasing who you are can really get you a lot of places.”

Braiding Sweetgrass is filled with teachings about gift-giving – to the Earth, to other species, to each other. Dwairi commemorated this by offering Kimmerer a gift.

“I knew that I wanted to give her something. She talks about gifts in her book and I wanted to give her a gift because she gave me the gift of so much knowledge and so much inspiration.”

Her gift came from Palestinian heritage. She hand-stitched a tatreez motif of sweetgrass and laid it in a pin. She placed za’atar – prepared in Jordan by her grandmother with sumac, homegrown and hand-dried thyme, and toasted sesame seeds – in a little cloth pouch. She described how za’atar is eaten with pita bread and olive oil, and is deemed a “brainfood”; her mother would make her “za’atar sandwiches” before midterms.

“I decided to make her a bundle of sweetgrass. That way I would be using Palestinian-style tatreez, something from my tradition and heritage, and sweetgrass, something from her tradition and heritage,” said Dwairi. “I just told her that she is such an inspiration to young women. I hold my tradition dear to me. I’m obviously, visibly a muslim but I also wanted to hold onto the fact that I’m Palestinian because I think Indigenous solidarity all over the world is needed.”

Dwairi, studying to become an environmental scientist, is working on an undergraduate thesis on agricultural resistance in the Gaza Strip. A 2024 UN report states that 70% of Gaza’s crop fields have been destroyed by Israeli forces; famine across all of Gaza looms as genocide continues. Dwairi wore her keffiyeh when she met Kimmerer, a symbol of Palestinian resistance bearing patterns of olive trees, roads, and fishnets.

Kimmerer accepted her gifts lovingly.

“She held my hand,” said Dwairi, “and said “Aren’t we so lucky to have each other?””