“There’s no Pride without Palestine”: Perspectives on pinkwashing

Incé Husain

Sat March 22, 2025

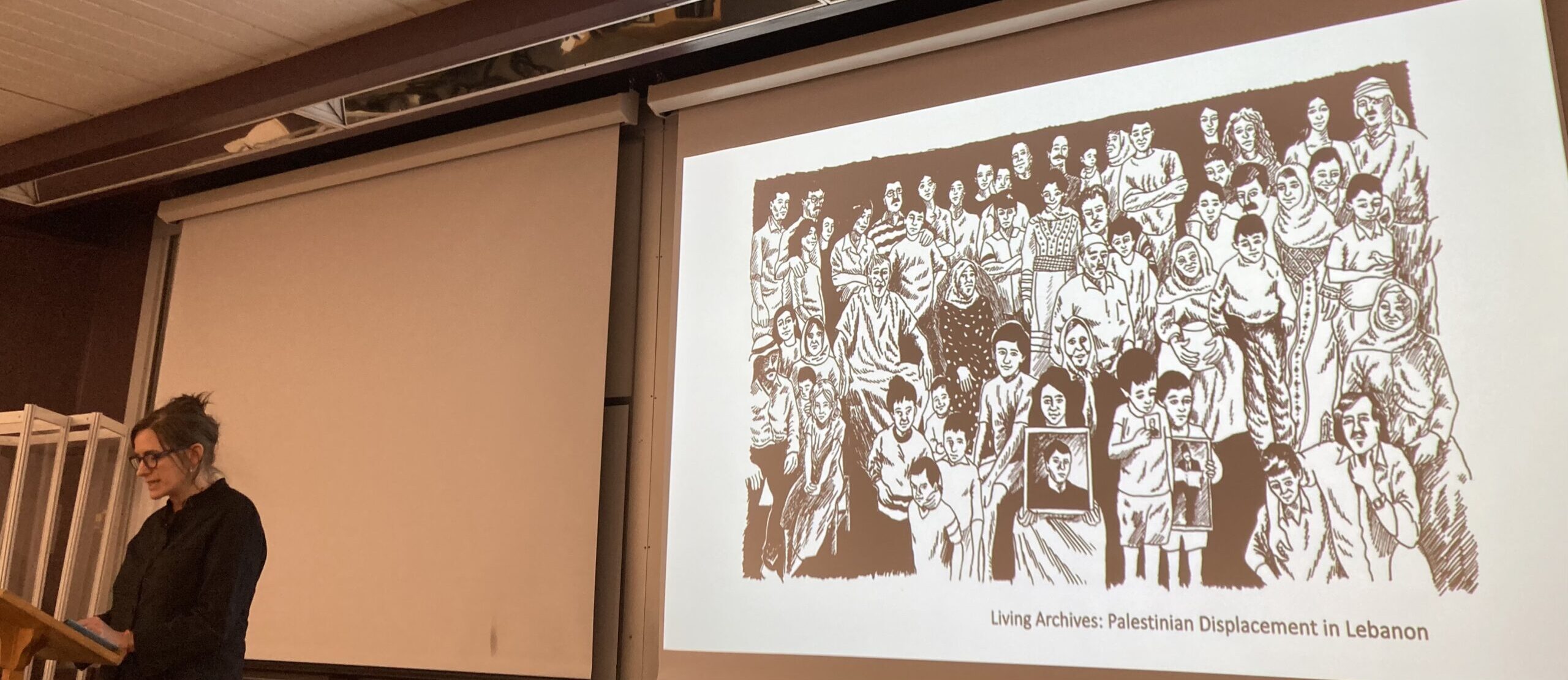

On Tuesday, March 18th, two Israeli youth spoke to a Queer Theory class at Western University about queer feminist critique of Israeli militarism and pinkwashing.

“Pinkwashing” refers to the portrayal of Israel as “more humane, modern, and accepting” than the Arab world when it comes to embracing the queer community, and using this portrayal currently to morally justify the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Einat Gerlitz, twenty-one years old, and Tal Mitnick, nineteen years old, refused to enlist in the Israeli military on grounds of pacifism. Both were imprisoned by the Israeli military and faced a slew of death threats and insults from their society.

Both argue that queer solidarity is entangled with Palestine solidarity.

“Israel is seen as this gay haven for human rights in the Middle East. And while there has been a lot of progress over the past few decades in queer rights in the Israeli state, it’s important to notice that, first of all, we don’t have the same rights for everyone in the queer community, and also, pinkwashing is used to cover up the crimes that Israel does in Gaza, in the West Bank, the oppression of the Palestinian people,” says Gerlitz. “It’s used to shift the focus from the crimes that are being done to this facade of human rights that Israel tries to put on. It’s the regime’s interest to divide us so that we don’t make those intersectionality connections, to have the Israeli Jewish queer community not make the connections with other oppressed groups around us. Oppressing and brainwashing in order for us not to see intersectionality is in the regime’s interest.”

Gerlitz came out as a queer woman when she was fifteen. Since then, she has been involved in queer youth movements in Israel. Moving in these activist circles shifted her view of feminism away from an “Israeli feminism” that emphasized empowerment within the military.

“The liberal feminism that I grew up on in the Jewish secular society is a feminism of talking about equality and how important it is for women to have equal rights. But the biggest avenue for that is the military. Breaking the ‘glass ceiling’ in the military is seen as one of the most important things in Israeli feminism,” says Gerlitz. “I don’t think that our feminism struggle should be inside of the military and to be part of the militarist and patriarchal system. I think my feminism is fighting outside this system to change it, not being a part of it.”

Mitnick says that the “same groups that want to erase trans identity and queerness in the world are the same groups that are trying to erase Palestinian identity”.

“It’s the same system of erasing anyone who talks against the hetero-normative, militarist, patriarchal status quo.”

Mitnick also considers pinkwashing to be part of Israel’s “facade of civil rights” that maintains its “strong connections with the West”.

“Having this image of protecting Western values is not only the difference between the kind of evil we’ve been seeing recently – it differentiates itself from something that we can very easily condemn,” says Mitnick. “In Western values, we know we need to fight against discrimination, but when it comes to othering Brown and Black people living in the land, it’s less accepted to stand up for those rights… because of the prejudice against [them].”

***

Cailin and Rudie, two community members who attended Mitnick and Gerlitz’s speaking event later that evening, first became aware of Palestine through queer spaces.

In 2013, Cailin heard about a group called “Queers Against Israeli Apartheid” in Toronto. Cailin says the group strived to be part of Toronto Pride, but city councillors and the “corporate structure” of Toronto Pride “vehemently opposed” their inclusion. Formed in 2009, the group ceased to be a formal organization in 2013; Cailin says they were financially suffocated by Pride in their first couple years of operation.

“I know a lot of queer Jews in Toronto, and that was a big part of my community there as well, including some queer Israeli Jews,” Cailin says. “I think, in most cases, they were people who didn’t actively, outwardly refuse the same way [Gerlitz and Mitnick] did, but found other ways to get through the system with the minimal amount of participation and feeding the machine as possible.”

Rudie’s partner lives in Israel and is resisting military enlistment. Communities of Palestinians and Muslims in London also opened his eyes to Palestine solidarity.

“I was seeing [Palestine] a lot on the news in queer spaces. I had not known anything about that till now,” says Rudie. “When you’re a queer person, you can’t just fight for queer rights and not think about other people being affected by Zionism and racism. There’s no Pride without Palestine.”

Siddharth, another community member at the evening event, shared that it was novel to hear about “the dynamics [Israelis are] having amongst themselves”.

“Something I really didn’t hear about before is learning about Israeli civil society, and what are the dynamics they’re having amongst themselves. That’s just not a perspective you hear about,” says Siddharth. “Of course, the focus should be on Palestinians, but it’s very insightful to understand what kind of internal dialogue feeds into [Israeli views] and what are those conversations — how people can also have some perspectives when talking to Zionists and people who have grown up in Israel.”

Rudie added that “older people” attended the event too, potentially undoing age-old media narratives they may have heard that conflate anti-Zionism with antisemitism.

“In the media, there are a lot of people who will say that being anti-Zionist is being antisemitic, which of course isn’t true,” says Rudie. ”If you’re just sitting at home looking at the news, all you’ll see is this misinformation. But there are older people who are coming to these events and trying to be informed.”

Cailin admired Gerlitz and Mitnick’s unwavering moral clarity.

“I was just really inspired to see young people who have that level of political consciousness. Not just political consciousness in general, but specifically in the belly of the beast, in this extremely indoctrinating, repressive, fascist society, that they were able to escape that,” says Cailin. “I think we have a lot to learn from people who are able to do that. I had a lot to unpack and deprogram even just growing up in this society, and get past the relatively shallow layers we have of that here.”

***

Samah Al-Sabbagh, a Palestinian-Canadian and president of Canadian Palestinian Social Association, has never lived in Palestine.

At Gerlitz and Mitnick’s evening event, she shared that her parents moved to the Gulf and then she came to Canada at twelve. She inherited an identity card for Gaza — permits that allow Palestinians entry into Gaza — from her parents, and obtained cards for her children, too. She took her children to Gaza for ten days.

“I started loving this land that I’d never seen,” says Al-Sabbagh. “Nobody taught me. I just saw my parents, I heard, I investigated, I read. The term I coined is ‘intergenerational love of the land’. You don’t have to live there.”

In 2010, she tried to take her family to the West Bank and Israel. The military refused.

“You’ve entered Gaza through Egypt, so you’ve supported Hamas,” the soldier had said.

He’d said that her family would be granted entry if she surrendered all Palestinian identity cards.

“So it’s either: we erase you, you forget about your land, and we’ll let you in. But if you don’t forget about your land and you don’t submit to our power, we won’t let you in,” she says. “I see in his eyes and his words that they hate the fact that we really love our land… We long for a Palestine that is welcoming of anyone who wants to identify with the land.”

With files from Emmanuel Akanbi