“Where Olive Trees Weep”: Roots of injustice and resilience in the West Bank

Incé Husain

Sun February 16, 2025

“I felt anger towards what the people on the screen were going through. Anger that this injustice – all of this – is still happening. Anger that all of this exists,” says Western University student Kamil Zerdoumi after viewing a film screening of Where Olive Trees Weep at King’s University College on November 29th, 2024. “It made me more aware of this huge, huge imbalance between [the] rights that Israelis and Palestinians have, and made me more fervent in Palestinians getting more rights and equal treatment and more justice, and less forgiving in any attempts to try and be a centrist. Every Israeli soldier that has committed these awful, awful crimes must be brought to justice. Must. Not ‘if we can’. Must. All the damage that was done to the Palestinians must be paid back. I used to be a bit gentler – that there will be peace in the end. But that film says ‘you will never have true peace until there is actual justice’.”

Where Olive Trees Weep was filmed in May 2022 in the occupied West Bank. European directors Zaya Benazzo and Maurizio Benazzo were invited by physician Gabor Maté to a trauma healing workshop Maté was holding for Palestinian women who had been incarcerated or tortured in Israeli prisons. Their visit culminated in the film.

“[Maté] said ‘come with me. I’m not sure what you can film, but come along’,” said Zaya during the film premiere. “It’s a dire time to be releasing the film. And yet, it feels timely, and we hope the film will give more context to people who don’t know what’s happening today…Israel keeps targeting all the cultural centres, the libraries, any kind of record of people’s lives, any remnant and traces of their roots to the land have been intentionally wiped out. So genocide is not just mass murder. It is also the intentional erasure of whole society and culture. And this is happening also in the context of a very well-coordinated misinformation campaign.”

Released in 2024, the film documents personal stories of West Bank Palestinians the directors met. All are marred by violence and a relentless fight for liberation. Ashira Darwish, who worked as a journalist in Palestine for fifteen years, describes being arbitrarily hauled into prison rooms for torture, beaten unconscious, hit so hard by an Israeli soldier that she was paralyzed. She urged the world to “not put a penny that goes to the bullet that shoots our children”. Ahed Tamimi, who grew up in the village of Nabi Saleh, remembers being searched by Israeli soldiers as a child, visiting her wrongfully-imprisoned father and touching his fingers through the bars, seeing her fifteen-year-old cousin get shot in the head at a protest, and slapping an Israeli soldier in retaliation – footage that went viral – that led to her seven-month detainment at sixteen years old. Hassan Mizher, a high school student from the Dheisheh Refugee Camp, was arbitrarily shot by Israeli forces while going to school; paraplegic, he reminisces on the freedom of going up the stairs.

Stories like these continue unbroken for an hour and forty-three minutes.

There was no applause at the end of the film screening.

“I did not realize it was going to be this intense,” says Zerdoumi. “It was like a horror story after a horror story after a horror story after a horror story. And it never stops…I was sitting there pinching myself just a little bit, or just grabbing my arms.”

Perspectives from non-Palestinian human rights activists including Maté, Israeli journalist Amira Hass, and Israeli activist Neta Golan who is a member of Israelis Against Apartheid, were interspersed throughout the film.

A question on the film’s FAQ page asks “why do you only present the ‘Palestinian side’?” The answer reads:

We are well aware of the complexity of historical details, the intricacies of opposing narratives and the convolutions of psychological projections. We expected to find the same complexity on the ground: a multifaceted scenario of shared responsibility and denial. Within a day or two, like anyone who has traveled to those parts, we found out that the big picture is surprisingly clear: a brutal settler colonial project imposing a very harsh form of apartheid and bent on ethnically cleansing an Indigenous population by all available means.

“The film has a life of its own,” said Maurizio during the film premiere. “It’s an absolutely mixed feeling — of feeling honoured to be able to be the instrument of this movie, to have it take birth, and on the other hand, it’s painful to have to be the instrument of such a film.”

As part of the film’s twenty-one day premiere, the co-directors held conversations on Palestine with historians, activists, artists, journalists, and spiritual teachers. Proceeds from the film are sent towards humanitarian aid in Gaza, trauma healing in Palestinian communities, the planting of olive trees in Palestine, and bringing the film to larger audiences.

At King’s, the film screening was followed by a panel discussion with Palestinian and Indigenous community members. They shared how they maintain connections to Palestine, the role of storytelling, and human rights work happening in London.

“My parents were not allowed to raise me in Palestine, and so they raised Palestine in me,” says one speaker.

He shares the preservation and celebration of identity that comes through language, food, and art. Cultural foods like za’atar and maqluba are “designed to be communal experiences,” uniting families and friends in a way that gives a sense of “raising Palestine in us.”

“Recognize those areas of culture that you’re able to preserve — whether its language, in food, in art, whatever it may be — and hold onto that like your life depends on it, because for some people it does.”

Another speaker warmly discussed a website called Palestine Remembered, rich with documentation of “every single city, every single village that you can think of”. He found close to twenty, lengthy interviews with people who survived the 1948 Nakba, and a map of his village. He showed the map to his father, who recognized hills, fountains, their ancestral home and the homes of friends from stories he’d heard.

“I made it my personal goal to research. I highly suggest to every other Palestinian born in the diaspora – maybe you’re like me, your parents have never stepped foot in Palestine – to really do the research, learn your roots, learn about your village, learn about the families that were there, stories that people can share from your village,” he says. “It feels so weird because you know that this person [on Palestine Remembered] has probably sat down and talked to your great-grandparents.”

A Lebanese speaker with Palestinian roots describes a “very dear” short film she created about a pomegranate plant from Haifa, Palestine. Her late grandfather carried the plant with him when he was forced to flee during the Nakba; her eldest uncle dedicated his life to its preservation. The plant travelled from Palestine to Lebanon to Cyprus to Canada.

“Through that film and the process of getting back in touch with those stories through my uncle, I was not only able to bond with my uncle and create something that can basically live a long time in my family, but it was very empowering and very special to see it just be, without having to explain so much,” she says. “Storytelling also helps us process our histories, our traumas. And then it bridges the gap between personal and collective memory. It’s something that oppressors can’t touch for too long, that’s something that can never be taken away.”

A speaker Indigenous to Turtle Island brought up similarities between Palestine and Turtle Island.

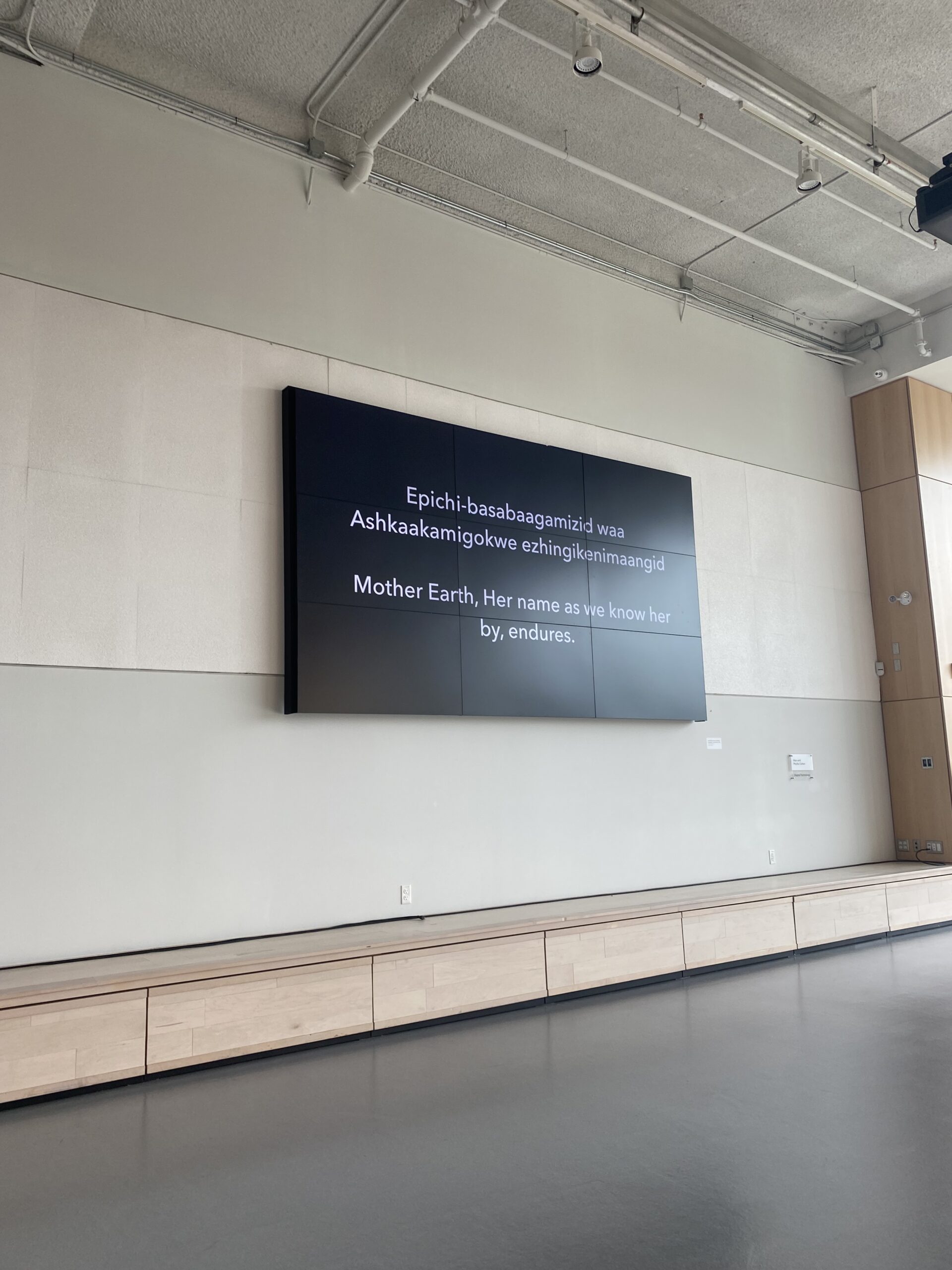

“Here on Turtle Island, we are reckoning with our own settler colonialism and ongoing genocide against Indigenous nations,” he says. “There are commonalities [with Palestine] – theft of land and resources, the silencing of stories and attempted erasure of culture and identities – while also witnessing land defenders and elders and knowledge keepers and communities from many Indigenous nations actively resisting and reclaiming our Indigenous languages and ceremonies and ways of knowing.”

The Palestinian speakers shared that it’s necessary to “sit with the discomfort” of recognizing that they, too, are settlers on Turtle Island.

“I fully believe that in order for me to be advocating for my people, if I’m not doing my part to recognize and learn and research about what happened on Turtle Island, then my activism work is not doing justice for the lands that I am on,” says one speaker. He shares news of an Indigenous boy’s murder in September 2024 by the RCMP; fifteen-year-old Hoss Lightning was shot by police officers, unarmed and trying to flee.

“If you really look into it, you’re going to see a lot of commonalities between the [Israeli] forces we watch and what they’re doing to innocent Palestinians and the way that the forces within Turtle Island oppress and brutalize people who are speaking up for justice.”

Another speaker shares that he didn’t associate with the reality of being a settler on Turtle Island “for a long time”.

“I don’t view myself as a settler — that’s not an identity I grew up with, that I’m a settler, I grew up on stolen land. My own family was forced to come here because they were ethnically cleansed from their own land. What is my culpability in that?” he says. “The reality is you’re here. And so the question is: what are you going to do about it? Are you going to contribute to the erasure of Indigenous people here? Or are you going to push back against it? Are you going to push towards the restitution of rights? Or are you going to ignore it and be a bystander?”

The speakers encouraged all to become involved in human rights activism for Palestine, listing Western University student groups such as Muslim Student Association, Palestinian Cultural Club, Climate Crisis Coalition, and local group Canadian Palestinian Social Association of London. One speaker urged all to “step out of your comfort zone a bit and put yourself out there”.

“I think there’s so much more that [non-Palestinians] can do than a lot of Palestinians can do. And I’ve tried to get this message across to some of my non-Palestinian friends who are hesitant to engage with this topic,” says one speaker. “You talking about this issue to your close friends and family is going to impact them much more than if I were to talk about it. Whatever made it click for you is probably what will make it click for your friends and family as well.”

Zerdoumi learned about the film screening at King’s from a friend. He had already been interested in documentaries about Palestine; born in Algeria, he felt a tie to Palestine from Algeria’s 132 years of French colonialism.

“In Algeria, the whole Palestine question — it’s not a question. Palestine is Palestine and Palestinians are Palestinians,” he says. “We have this same trauma of colonialism, it’s just that for us, we have the luxury of saying ‘oh, it was in the past now’. But for Palestinians, it’s still ongoing.”

He remembered film scenes of Gabor Maté leading a trauma healing circle for Palestinian women who had been incarcerated or tortured in Israeli prisons. One woman asked Maté: “why do we have this feeling of freezing?” Maté explained that the body reverts to three responses when under threat: to ask for help, to fight, or to hide. But if there is no help, if you can’t fight back, and if there is nowhere to run, the body ‘freezes’, offering a protection from pain where it couldn’t from the situation.

“[The healing circle] was the most powerful to me,” says Zerdoumi, recalling the hardships of French colonialism, including a period of time where there were “more deaths than births”. “But we still had our moments where we would gather round, sing, celebrate life. What that film pointed out was that being able to live — live not survive — is one of the greatest acts of resistance that you could truly have.”

In another scene, a Palestinian insisted that they must not “over-victimize” themselves. Zerdoumi resonated with this. Victimization is acknowledgment of an injustice; over-victimization is to erase all other facets of a person. Similarly, Zerdoumi says that the term “Palestinian refugee” has a submissive connotation, undermining the reality that “these are brave people who fought back” as politicians, resistance fighters, and more.

“A victim is someone who has been heavily impacted by an injustice,” he says. “Over-victimization takes away agency, dehumanizes people. You’re only known as a victim and that’s it, instead of a whole complicated human being. Just because you’ve been a victim of something doesn’t mean that crime defines who you are, that you are just the ripple effect of that crime in that situation. It erases your identity.”

In its emphasis on personal narratives, Where Olive Trees Weep re-instilled impact into words like “apartheid” and “colonialism”. Zerdoumi says these loaded words can come to carry oversimplified, detached meanings if they are never understood alongside lived experiences.

“You learn about apartheid, you read about it, but you never experience it. We don’t live in a system we can equate to apartheid here. Yes, you’re disgusted by it, but you don’t fully grasp it until you’ve lived through it or you listen to someone who has lived through it,” says Zerdoumi. “You get used to hearing about violence. But that film pushed that away and told you ‘listen, this is the experience. Feel it.’”

The title of the film honours the opening lines of the poem an alsũmūd” (“On resiliency”) by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, published in 1964:

If the olive trees knew the hands that planted them, their oil would become tears.