“A small window into dehumanization”: Palestinian-Canadian doctor on the destruction of healthcare in Gaza

Incé Husain

Fri March 7, 2025

“Do you know how hard a kid fights when you bring a needle to their face and start cutting into it? Do you know how much strength they suddenly have? You can’t believe where it even comes from? Can you believe the screams that they deliver, when you try to suture them up? It’s crazy, it’s haunting. Truly, truly haunting,” says Palestinian-Canadian doctor Tarek Loubani. “The Israelis were always selective about painkillers. They’d never let painkillers through.”

Loubani remembers suture rooms in Gaza full of wailing children. Half of Gaza’s population are children; they are the majority of those injured by Israeli forces. Local anaesthetics in Gaza are rare, barred by the illegal Israeli occupation and near-impossible to smuggle in. Nurses would restrain the wounded, thrashing children as doctors approached. Parents would drape their bodies over them.

“Where’s the local?” Loubani had asked a doctor when he’d first entered the suture rooms. “I don’t want to stitch some kid who’s three years old and has a gash on his face without local anesthetic.”

“What are you talking about?” The doctor had replied. “We haven’t seen local anaesthetic in months.”

Since the start of the genocide in October 2023, UNRWA reports that 10 children lose one or both legs daily from operations conducted without anaesthesia. At least 18,000 children have been killed.

Newborns were left to die.

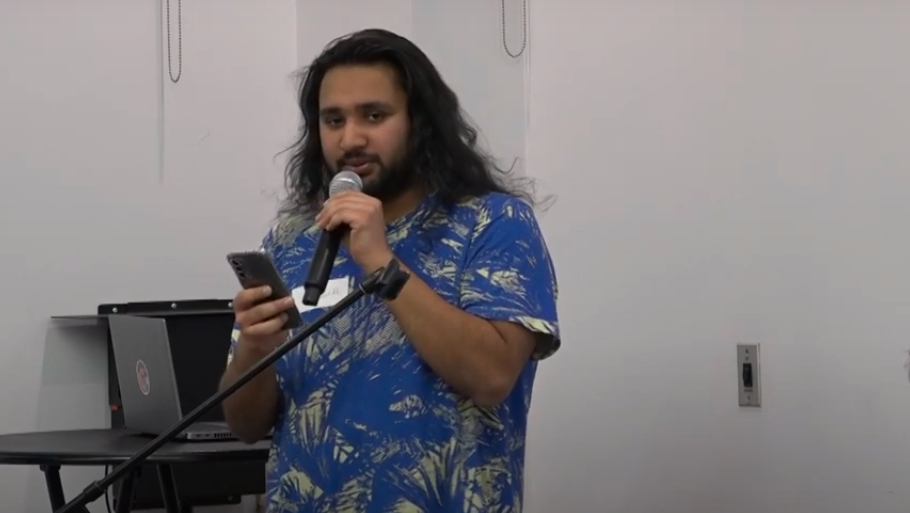

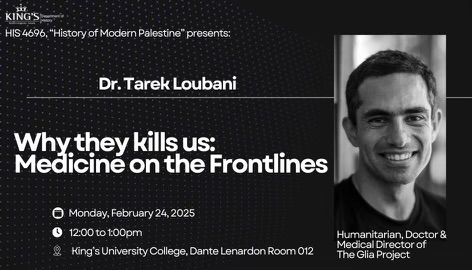

“Some of you may have seen these disturbing, disturbing images of tiny little babies in the neonatal intensive care unit in one of the pediatric hospitals,” Loubani continues, addressing a room of about twenty people in his talk “Why they kill us: Medicine on the frontlines” at King’s University College. “Their parents and nurses were forced to abandon them, and then the Israelis turned off the power and let those children rot where they lay.”

Loubani says every component of maternal health is ”under fire”. In 2014, Gaza’s water wells were bombed, leaving thousands without access to clean drinking water. Birth defects increased following the attacks. Pregnant women are regularly removed from ambulances, forced to deliver at checkpoints.

“(Israeli forces) have a particular disdain and hatred for pregnant women,” Loubani says. “Pregnant women create what Israelis call “the demographic threat”. Palestinians aren’t people – women who love their children, who want to have children because they are deeply in love with life. They are a weapon to Israelis. A weapon that produces more weapons… They are the aircraft carriers of the Palestinian army as far as the Israelis are concerned. And so they attack maternal health the hardest, the absolute hardest.”

A UN report from May 2024 states that Israeli forces’ attacks on healthcare increased miscarriages by 300 percent, and denied 690,000 women and girls access to menstrual hygiene supplies. Some took contraceptive pills to stop their cycles, unable to bear them with privacy and dignity. Israeli forces also destroyed Gaza’s largest fertility clinic storing 3,000 embryos.

“If you don’t see Palestinians as human beings — like for example, if you had a bunch of rodents running around, and you saw one that was going to make ten more rodents, you would kill that one first. We are their rodents.”

In 2018, amidst a pinnacle of nonviolent Palestinian resistance called “The Great March of Return”, Loubani was shot in both legs by an Israeli sniper. He had been identified by Israeli forces as a ranking physician, clad in medical gear and tending to the injured.

“The Israelis had a protocol where they would identify the leadership of medical teams and rescue teams and shoot them,” says Loubani. “I was the first person shot at that protest from the medical teams. Already, by the time I was shot, there were probably one or two hundred people shot… there had been half a dozen people killed.”

Pain seared through his legs. Bullets move faster than the speed of sound; the pain ignites before the shot is heard. The Israeli sniper had attempted to “kneecap” him, shatter his bones. The medical team gathered around him as he fell.

“As I fell to the ground, the team had already started looking around. They mobilize fast. Usually they start running before they know who’s shot and wounded,” says Loubani. “They created a protective cover around me. The protesters, the medical teams, everybody, just shield the person who is wounded so that they don’t get shot again.”

In the 2014 war, Loubani says about a thousand Palestinians died of blood loss; half of them took at least 30 minutes to die. Tourniquets to bind their wounds would have saved them. But tourniquets are barred from entering Gaza, “blocked by the Israelis on one side and by the Egyptians on the other”.

Instead, tourniquets in Gaza are few and makeshift: a piece of cloth and a stick, or 3D-printed and mostly made child-size with over half of shooting victims being children under fourteen. When Loubani was shot, there were only about fifty tourniquets left.

“Do you want a tourniquet?” asked Musa Abuhassanin, a paramedic who Loubani had worked with for many years.

Loubani said no.

“I knew I didn’t need it, in the Palestinian sense. In Canada, if a patient came to me with a gunshot like the one I had, let alone two, and they didn’t get a tourniquet, the paramedic involved would probably lose their job. But in Palestine, (Musa) knew that I did not deserve one of those very, very precious tourniquets. But he asked me anyway. I looked at the leg, I saw the blood, and I said no.”

Loubani was transferred to a trauma stabilization site, offered an Advil, and told to “wait till more people come” before an ambulance would head to the hospital. A stream of gunshots later, five wounded protesters joined him. They all entered a cramped ambulance.

The hospital was “sheer chaos”.

“Listen,” said the doctor, one of Loubani’s former students, who was treating hospital patients. “Because it’s you, I will take care of you in any way you want, but could you sew yourself up? It would really help us out.”

Loubani cleaned himself, sewed shut his gunshot wounds, hoped for the best, and waited.

A paramedic near him held a walkie talkie, turning the volume down to hide the messages.

Loubani approached him, demanding to know what had happened.

“Musa has been shot,” the paramedic said.

Musa was the father of four children, around the same age as Loubani. His mother, a protester, had heard his screams and ran to him.

The medical team, trying to reach him, had been shot and restrained by Israeli forces; only when Musa stopped writhing and stilled in death did they let the team go to him. He died in his mother’s lap. Over the radio, he had said again and again: “I can’t breathe”.

“What is it about a soldier that makes them point at an area while someone is squirming, dying, until they stop squirming and dying, to allow other people to pick them up?” says Loubani. “Those individual decisions that these soldiers make on the ground — they are not aberrations. There is nothing individual about the decision of the sniper who shot me, the sniper who shot Musa, the sniper who shot his rescuers. Those decisions are deeply founded and embedded in an entire system of control, domination, and extermination.”

A UN report from January 2025 states that over 1,057 Palestinian health and medical professionals have been killed by Israeli forces since October 2023. Another UN report states that Israeli forces have completely destroyed all but sixteen of thirty-six hospitals in Gaza; and WHO counted 654 attacks on healthcare facilities.

Senior paramedics, like Musa, often gravitate to the front lines in hopes of granting junior paramedics a few more years of life and relative safety from trauma.

“Ask yourself: what did you feel the last time you killed a mosquito?” Loubani describes dehumanization. “A mosquito that bites and takes your blood is literally taking a drop of your blood to feed its children. They cannot complete the reproductive process without a tiny bit of your blood. And yet you felt nothing. That’s kind of a small window into dehumanization.”

Gaza is very small. It would fit into London at least two and a half times. In 2022, its population was nearly 2.2 million, with 40.5% being children under the age of fifteen. In 2021, its literacy rate was 97.7%, among the highest in the world. Loubani says it has the highest PhD rate per capita. The medical expertise in Gaza is very high; Loubani says every medical student in Gaza “would trump medical students here in terms of raw examination taking”.

Since October 2023, Israeli forces have dropped 100,000 tons of explosives on Gaza. This is the equivalent of eight nuclear bombs. All eleven universities in Gaza have been destroyed.

In October 2024, The Cradle reported that Israel and the US plan to erect concentration camps across Gaza, where Palestinians would be walled in “neighbourhood bubbles” based on “biometric identification” and guarded by CIA-trained mercenaries.

Law for Palestine, a non-profit human rights organization based in Sweden and the UK, compiled a database of over 500 statements of genocidal intent by Israeli politicians, journalists, military personnel, and other public figures. This database was used by South Africa’s legal team in 2024 to fight a case at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza.

There are no innocent people in the Gaza Strip, reads a quote in the database by a member of Israel’s parliament.

They are animals, they have no right to exist, reads another, by Israel’s minister of education.

“Our existence as Palestinians is the enemy of Israelis,” says Loubani. “For Palestinians, their very existence is the strongest form of resistance. Their very survival day to day is a huge form of resistance. And so the Israelis understand that if (doctors) perpetuate that survival, if we stop injury and death, then that’s going to be a real problem. Every single Palestinian, whether they are in Palestine or in the diaspora, fights for the liberation of Palestine in their own way.”

Ingenuity is the only way to make it in Gaza. Loubani says disposable healthcare items — like syringe tips and gloves — are selectively barred by Israeli forces. Doctors almost always wear a single glove, exposing themselves to potential blood-borne illnesses. When scarce, gauze — a word that comes from “Gaza” — is manufactured by pulling out hundred-year-old looms, replicating the ancient Roman technique of making gauze. Medical equipment is recreated using 3D-printing. The Glia Project, for example, established 3D-printing facilities in Gaza, and manufactures equipment such as stethoscopes and tourniquets; Loubani is its Medical Director. All plumbing is made from recycled plastics; organic materials and plastics are separated and resourcefully used when they reach Gaza’s dump. Video-conferences over Zoom flourish, with Palestinians barred from attending international conferences due to the air, land, and sea blockade imposed by Israel since 2007. Books for scholarly pursuits are smuggled in. Infrastructure in Gaza is unusually sturdy, built to take bombs. Loubani says a bomb that would obliterate a building in London would only make a hole in a building in Gaza.

“If you reinterpret the Israeli attacks as being devoted to destroying Palestinian life, it starts to make sense,” says Loubani.

He explains Israel’s list of “dual-use” items that are barred entry into Gaza. According to Israeli non-profit organization Gisha, founded in 2005 to advocate for Palestinian human rights, “dual-use” items are “civilian goods that could also be used for a military purpose, even though these items are not defined as dual-use according to international standards”. A partial list of dual-use items produced by Gisha in 2010 includes chocolate, nutmeg, and toys. He says Israeli forces would raid houses and spill all the za’atar – a Palestinian spice mix made of sumac, thyme, and sesame seeds – “like it was cocaine”.

During the “Great March of Return” protests where Loubani was shot, 195 Palestinians were killed and around 29,000 injured with live ammunition within a year. The protests were committedly nonviolent; every Friday, unarmed protesters marched to the perimeter fence separating Israel and Gaza – beyond which lay their ancestral homes – demanding an end to the siege on Gaza and the right of return. Palestinian families gathered in encampments erected 600 meters from the fence, filled with poetry readings, musical shows, and soccer games. The protests lasted from March 30th, 2018 till the end of 2019, with a “rich morality” of “self-sacrifice” : protesters would take injuries while delivering none.

But Palestinians were given no rights.

“This is why the Palestinians walked away from peaceful resistance. They fully understand that there was no way to convince the Israelis of our humanity in this way,” says Loubani. “There is no such thing as a peaceful non-violent liberation of a country, it never happened, even one time, in any country, in history. We have to take our freedom by force.”

To view a partial transcript of Tarek Loubani’s talk, visit: “Six of us, stuffed into one ambulance, to go to a hospital. When we got there, it was sheer chaos”: Tarek Loubani’s Harrowing Story of Getting Shot in Gaza