“Six of us, stuffed into one ambulance, to go to a hospital. When we got there, it was sheer chaos”: A Harrowing Story of Getting Shot in Gaza

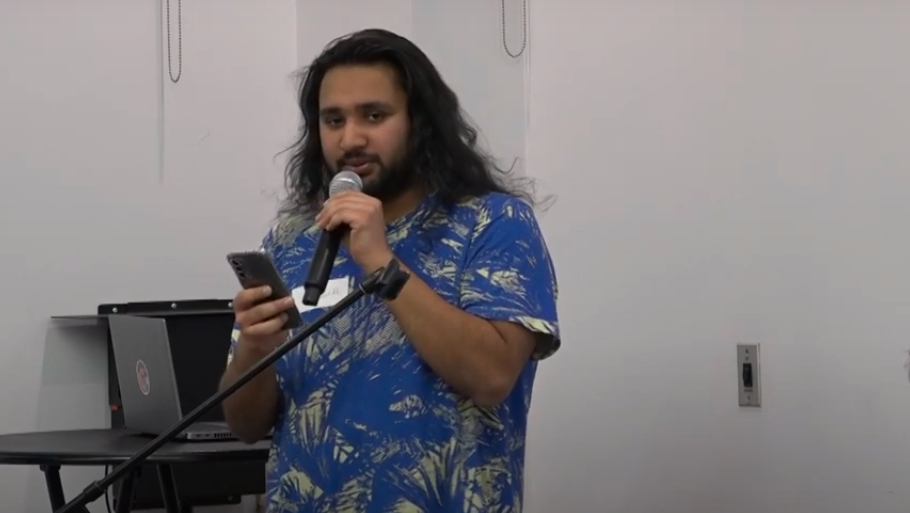

Tarek Loubani

Fri March 7, 2025

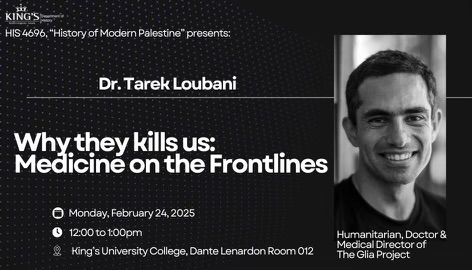

The following is a partial transcription, edited for brevity, of a talk given at King’s University College on February 24th, 2025 by Tarek Loubani, a Canadian doctor who has been involved in humanitarian medical missions in Gaza. Dr. Loubani recalls the time he was targeted and shot by Israeli forces while treating peaceful protestors during the Great March of Return protests of 2018-2019. He discusses how Israeli forces deliberately target Palestinian medical infrastructure and prohibit medicine and medical practitioners from entering Gaza.

I was shot in 2018 in Gaza. When I was shot, and I kind of fell to the ground, I didn’t really have time to think about all the times that I thought about getting shot.

I don’t know if you ever played out what would happen if you got shot. I don’t know if you have ever walked through it in your mind, as to how it would happen. How you would react, what would happen afterwards, and all the scenarios. But I can tell you, for me, when I finally got shot 16 years after the first time I saw someone get shot in Palestine, all I could really think was —

I have thought about this a million times, and this didn’t feel anything like any of the times I have thought about this.

So when I fell, when I yelled fuck, when I felt the searing pain going through my legs, the bullet was part of this procedure the Israelis had called “knee-capping”, where they would shoot the legs and hope to basically hit the bones in the leg. I didn’t know it at the time, but miraculously, even though both my legs were hit, none of my bones broke.

But I was on the ground. The first thing you do when you are a medical worker in this scenario is try to figure out where the wounded person is. Because I was part of the medical team, they looked around first. Because — I hope none of you guys have ever been between a gun and its target — but bullets are a funny thing. They travel faster than the speed of sound. So [when] the bullet hits, you hear it hit [your body] before you hear it get shot. It’s really disorienting until you get familiar with it. Because basically, it hits the ground, let’s say, and it feels like the ground was shooting at you.

The first thing I heard — or anyone hears — was [when] the bullet hit the ground near me, having no trouble going through my leg. Then, as I fell to the ground, the team had already started looking around. They mobilized fast. They created a protective cover around me. The protesters, the medical teams, everybody, just shield the person who is wounded so that they don’t get shot again.

This one paramedic, a man who I had worked with for many, many years at this point, a man named Musa, came and sort of hung over me and was like [in Arabic], “Oh, doctor, what have you done to yourself?” — making light of the situation. We are all a little messed up in the head. You can’t be out in a battlefield taking care of patients all day if you’re not a little messed up in the head.

[Musa] starts making decisions. What are the odds that this guy is going to die? What are the odds that I need to escalate treatment? What are the odds? Because I wasn’t going to be the only person who was shot. There were other people getting shot. And if they decided to devote a bunch of resources to me, they couldn’t devote them to the others.

And the other decision he had to make was what to do about the tourniquets?

We had developed inside Gaza, tourniquets that we could build inside Gaza. Because tourniquets are what the Israelis call dual-use items and are strictly forbidden in the country.

So there were no tourniquets in Gaza. And in the 2014 war, when we were finally able to assemble all the statistics, what we realized was that half of the 2,000 people who died, died of what we call exsanguination — [a] fancy word for they bled to death.

Half of them took at least half an hour to die. That means they sat there, waiting for death, for half an hour. Those were what we would have considered the highly salvageable cases — the cases we could potentially treat and stop the death of exsanguinating injury in limbs. And how do we do that? A tourniquet.

Well, that’s a big problem. There had been no tourniquets in Gaza for many, many years.

How do you deal with that? We tried to smuggle them in, buy them, import them, ship them, and at every turn, we were blocked by the Israelis on one side and by the Egyptians on the other. So we started building them. Initially, what we called makeshift tourniquets—a piece of cloth and a stick. And eventually, 3D-printed tourniquets that were best in class.

And through printing, we found out that more than half of everyone who gets shot is children under the age of 14. You can’t use a tourniquet meant for a 20-year-old, burly American soldier in Afghanistan. You have to make them smaller, because the patients are smaller.

So you have to make decisions. And of the 50 or so tourniquets we had left for the day, Musa had to decide whether he was going to use another one.

He looked at my leg. He knew I didn’t need it. I knew I didn’t need it. I mean, in the Palestinian sense. In Canada, if a patient came to me with a gunshot like the one I had and they were not given a tourniquet, the paramedic responsible would probably lose their job. But in Palestine, he knew I did not deserve this very, very rare, very, very precious tourniquet. But he asked me anyway, “Do you want a tourniquet?” I looked at the leg, I saw the blood, and I said no.

So they packed it, they sent me off, and I waited in what we call the trauma stabilization area. So, how do we do it in Gaza? Gaza is small. Very, very small. Gaza would fit into London two and a half times, maybe three. So, it’s very, very small, and it’s basically set up like a band — that’s why it’s called the Gaza Strip. You can move long distances very easily, and yet, what we found is that people were dying because they weren’t getting access quickly enough.

So, during these protests, we set up trauma stabilization points. These are places where people were trained to do the most important things: basically, to stop bleeds, to open chests, and to perform these kinds of operations. I was transferred to one, and very quickly, they realized I was going to survive this — no problem. The bleeding was well controlled with packing. So, they parked me, offered me Advil — I kid you not, for a gunshot wound — and then basically said, “You’re going to have to wait until more people come.”

As I listened, there were gunshots, one after the other. People came, lined up beside me, until there were six of us. Six of us, stuffed into one ambulance, to go to a hospital. When we got there, it was sheer chaos.

The doctor who was treating the patients was one of my former students. He said, “Because it’s you, I will take care of anything you want, but, like, could you sew yourself up? Because that would really help us out.”

“Give me sutures, give me the cleaning, and I will sew myself up.”

Gunshot wounds are not supposed to be sewn up. They’re supposed to stay open. They’re supposed to be cleaned. But we were making risky decisions at that point. One of them was that no one was going to operate on this leg, so may as well close it and hope for the best. In my case, I was wrong. I ended up subsequently with a blood infection. But in that moment, it was the only thing I could do — it was the best decision I could make.

And while we were sitting there afterward, having sewn up and waiting for a few things to happen, the paramedic who sent me was sitting there, basically calling on his walkie-talkie. He was turning down the volume and trying to listen so that I wouldn’t hear it.

“What happened?” I asked. “What happened?”

And he said, “Don’t worry about it. Don’t worry. Don’t worry about it. Everything is fine.”

Of course, I knew that everything was not fine. Once the Israelis start shooting medical personnel, they’re not going to stop. I wasn’t a one-off. I didn’t wonder if they did this by accident. I knew they did it on purpose. And that meant the rest of my team was also vulnerable.

Personally, I am — there are different kinds of people — I am the kind of person who wants to know. So, I told him, “Don’t do that shit to me. Tell me what’s up, and I will process the information in whatever way I need to.”

And that is when he told me, “Musa has been shot.”

Musa Abu Hasanein was a paramedic about my age who had four young kids at home. When I first saw him in one of these protests about a week or two before this, I asked him, “What are you doing here?” He was so senior that he definitely didn’t need to be there. He definitely, definitely didn’t need to be on the literal front line. And he was like: “This seems like the pot calling the kettle black — what am I doing here? What are you doing here?”

And he told me he could not imagine himself being anywhere else because that is where the need was. He said, “I didn’t do paramedicine for almost 20 years so that I would just sit in a TSP or wait in an ambulance for somebody else to deliver the care.” He felt that his experience meant that he needed to be there. And you know what? Every time I asked a senior paramedic who was on the front lines, they would give me the same answer. In fact, very few junior paramedics were on the front lines because the senior paramedics wanted to protect them. They wanted to protect them from the mental trauma, protect them from the physical trauma. They wanted to protect them so they could live a few more years.

So, Musa was shot in the chest, and he started this process of death in that moment called tension pneumothorax. This is when there is a hole that allows air to escape from the lung but not any way for the chest wall to get the air out — every breath that a person takes is another step that brings them closer to death. Eventually, the pressure inside the chest is the same as the pressure inside the heart, and the heart can no longer pump, and the person will die.

The solution is very easy — in fact, so easy that I have done it multiple times in the time I had been in Gaza, even for that particular time. It’s as simple as this pen — I carry this pen because it’s got this metal shaft and a metal tip. So, that means when somebody has tension pneumothorax, all I need to do is stab the pen into the spot, create the opening, take the top off, and let them breathe off the tube until we get a definitive solution in an operating room or wherever.

I don’t know how many people I treated this way, but it was enough that people kind of made fun of the pen when they’d see it. If I lent it to somebody, they’d be like, “Whose blood is on that?”

And so, of all the people on the team in the field that day, there would’ve been exactly one person who could treat Musa, and that would’ve been me. There would’ve been exactly one person who could stop that tension. It’s not supposed to be fatal, and that would’ve been me. But I was in the hospital. And so Musa died.

Through the honest quirk, he died in his mother’s lap. She was a protester, she believed in the freedom of Palestinians. When he was shot, she ran to him. She heard him screaming. She knew it was her boy. She ran to him and sat by him, pinned down by gunfire. There were three other paramedics who were shot trying to rescue Musa. They were pinned down until he stopped moving, and when he stopped moving, that’s when the Israelis let the medical team in.

And on his radio, the whole time he was radioing: “I can’t breathe.”

I remember one of the medical teams afterward asking, “Why do they kill us?” He wasn’t asking on behalf of Palestinians. Every Palestinian in their bones knows why Israelis kill us. You interact with the occupation for three seconds, and you get it. Our existence as Palestinians is the enemy of Israelis, whether that be in Palestine itself, or in Canada, or where I was in Kuwait where I was first born, or in the refugee camps in Lebanon or Jordan. It doesn’t matter. There has not been one place that Palestinians have been safe from the occupation.

But what he was asking me was: “Why the medical teams? Why the medical teams?” All we ever taught them is that medicine is sacred. It is a sanctuary. It is a place that is completely exempt from every other rule of war or cruelty or depravity or attack from anything. There is not a single Palestinian doctor who doesn’t receive that lesson. And so, they found it hard to understand why we were targeted. Why were there 19 medics who have been shot? Why have there been thousands who have been killed over the years?

Why? Why do they kill us?

And you know why? The honest truth is — I don’t know. I don’t know. What is it that makes a soldier look through the sight of a gun, see a doctor who is obviously a doctor, and be like, “Yeah, that guy.” Or medics who are rescuing. What is it about a soldier that makes them point at an area while someone is squirming, dying, until they stop squirming and dying, to allow other people to come in and help? I don’t know.

But what I do know is that those individual decisions that those soldiers make — they are not aberrations. There is nothing individual about the decisions. The sniper who shot me, the sniper who shot Musa, the sniper who shot his rescuers — those decisions are deeply founded and embedded in an entire system of control and domination and extermination. That’s clear.

***

So, let’s go back for a second and talk about why we even have to discuss why Palestine is a low-resource center.

My family has six people—my immediate family, my parents, and four kids. Every one of us is a doctor. Lots of Palestinian families are similar. You see that there are lots of doctors within the Palestinian community. When we say low-resource, we don’t mean human resources. There are lots of very competent Palestinian doctors — in Palestine and outside Palestine. So, why aren’t I there? Why aren’t I there able to practice? Why isn’t my father there, who wants to be? Why isn’t my mother there, who wants to be? Why aren’t my siblings there, who all want to be? Because we’re all banned. We are all forbidden from entry into Gaza.

So, when we talk about the shortage of doctors there, that is a very, very specific, very, very deliberate decision on the part of the Israelis.

What about the equipment? When I first got there, I had a lot of learning to do. And one of the first things I noticed was this huge lack of equipment.

There were little children we had in a room, for suturing, and the room was the size of half the stage that is here. When I first walked by it, I could hear some kids wailing. I’m like, “Okay, what’s in that room?” They say, “That’s the suturing room.” Okay, well, these guys must be incompetent because they’re clearly not freezing these kids properly.

And so, after a while, I got to the suturing room. They’re like, “Oh, you want to do some sutures? Fine.”

“Where is the freezing? Where is the local anesthetic?” [I replied].

They’re like, “What are you talking about?”

“Where is the local? I don’t want to stitch some kid who is three years old and has a big gash in their face without local anesthetic.”

“Well, we haven’t seen local anesthetic in months. It comes in once in a while, but it’s rare.”

And so, I became one of the barbarians that I initially saw when I walked in. The nurses would hold the kid down. The parent would put their body on the kid.

Do you know how hard a kid fights when they bring a needle to the face and start cutting into it? Do you know how much strength they suddenly have? You can’t believe where it even comes from. Can you believe the screams that they deliver when you try to suture them up? It’s crazy. It’s haunting. Truly, truly haunting.

And the occupation—The Israelis were always selective about painkillers. They never let painkillers through. You could get a nuclear bomb before you got a vial of morphine. I tried to smuggle morphine in. Trust me, I tried in every way I possibly could. It’s a liquid. It looks like water. Not possible. And I swear to God, I could’ve gotten in a gun sooner than I got that morphine.

I think the whole point of destroying the medical system is because they are right about one thing. For Palestinians, their very existence is the strongest form of resistance. Their very survival day to day is a huge form of resistance. And so, the Israelis understand that if we perpetuate that survival, if we stop injury and death, then that’s going to be a real problem. Because the Israelis are kind of right — every single Palestinian, whether they are in Palestine or in the diaspora, fights for the liberation of Palestine in their own way.

Palestinians — I told you there are four kids in our family. I think my parents kind of wished they had double the number. It wasn’t even my mother who put a stop to it. My mother thought we should just keep going. But pregnant women create what the Israelis call the demographic threat. Palestinians aren’t people. Women who love their children, who want to have children because they are deeply in love with life, are a weapon to Israel. A weapon that produces more weapons. And in its own internal, kind of messed-up logic, it makes sense. If you don’t see Palestinians as human beings — for example, if you had a bunch of rodents running around and you saw one that was going to make ten more rodents — well, you would kill that one first. We are their rodents.

And if you kind of wonder about the dehumanization — sometimes I find it hard to empathize — just ask yourself, what did you feel the last time you killed a mosquito? What did you feel? Nothing.

A mosquito that bites you, that takes your blood, is literally taking a drop of your blood to feed its children. They cannot complete the reproductive process without a tiny bit of your blood. And yet, you felt nothing, right?

And that’s kind of a small window into the dehumanization. And so, that happens to pregnant women. They get offloaded from ambulances. They’re forced to deliver at checkpoints. It’s happened literally hundreds of times. Hundreds of times.

They’re poisoned. The water is unclean, impure, and so their children are born with defects. All the water filtration stations’ domes were bombed in 2014. The birth defect rate went up by ten times after that. The stillborn rate has quadrupled or quintupled after the 2014 war.

And so, what do you think happens to pregnant women? They are an integral part of the Palestinian army, as far as the Israelis are concerned. So, they attack maternal health the hardest. Every component of maternal health is under fire — right from the prenatal screening, the bloodwork required for that, and the tests required for that, all the way to the very end, until after birth, until neonatal intensive care.

Some of you may have seen these disturbing images of tiny little babies in neonatal intensive care. In one of the hospitals — one of the paediatric hospitals — their parents and their nurses were forced to abandon them, and the Israelis turned off the power and let those children rot.

Transcribed and edited for brevity by Amer El-Samman.